There was (and is) an enigmatic quality to [his work]…. which was not constrained by adherence to a style or association with a particular medium or rhetoric.

Anyone interested in contemporary Canadian art and its discourses during the 1980s would know of John Massey’s work and, at the same time, not necessarily know what the work was all about. It was discussed but not so readily seen. There was (and is) an enigmatic quality to it, due in part to the language and method of his inquiry, which was not constrained by adherence to a style or association with a particular medium or rhetoric. It was (and is) a way of thinking. Within a few years of his first self-staged exhibition in a Toronto warehouse in 1977, Massey had produced an astonishing range of work that included print media—a poster, a bookwork, and photolithographs—film, sculpture, photography, photographic objects, and installations that incorporated film, sound and dialogue.

I met John for the first time in 1987. He had returned to Toronto from a sojourn in New York, and was included in the inaugural exhibition at The Power Plant, where I was curator. Around 1992, I asked him to consider a solo exhibition at the Art Gallery of Hamilton. It took two years of regular discussion and pre-production to achieve. Rather than a survey it was, as we agreed, a positioning. There were four works spread over three gallery spaces: Black and White, a “peep show” using slide media and film; the first digital reconstruction of the film triptych As the Hammer Strikes (which has since been transformed again and still holds its merit and value), the first suite of The Jack Photographs; and a 1978 untitled plaster wallwork that had been executed only once before. This latter stretched eighteen metres across the width of the main gallery. John was there for the task of hand plastering.

Recently, we discussed his formative period. John stated that his main subject of inquiry has always been his own subjectivity, although he noted that this topic remains contentious and misunderstood. His practice, however, is not an academic exercise. He spoke about the continuing challenge of how to embody “space,” sometimes in the presence of an image, or architecture (a condition of being) and about not being restricted to an “aboutness.” Indeed, the title of a 1976 Massey installation work is The Embodiment, and a 1983 suite of photographic works is titled Body and Soul—A Cinematic Stasis (both are in the collection of the National Gallery of Canada). In the titles of the Jack suite of photographs, “he” awakes, feels, turns and touches. Massey’s titles are more than nominations, and, in turn, subjectivity and embodiment are not hollow phrases in his practice.

I salvaged a piece of the 1978 plaster work when it was taken away (destroyed… again), and still have it, not as art or an artful memento, but as a reminder that everything matters in the production and articulation of his work. John Massey uses all the tools that are necessary to him, and, dare I say, us.

Ihor Holubizky

JURY MEMBERS

Sarah Milroy

Roald Nasgaard

Margaret Priest

Stephen Smart

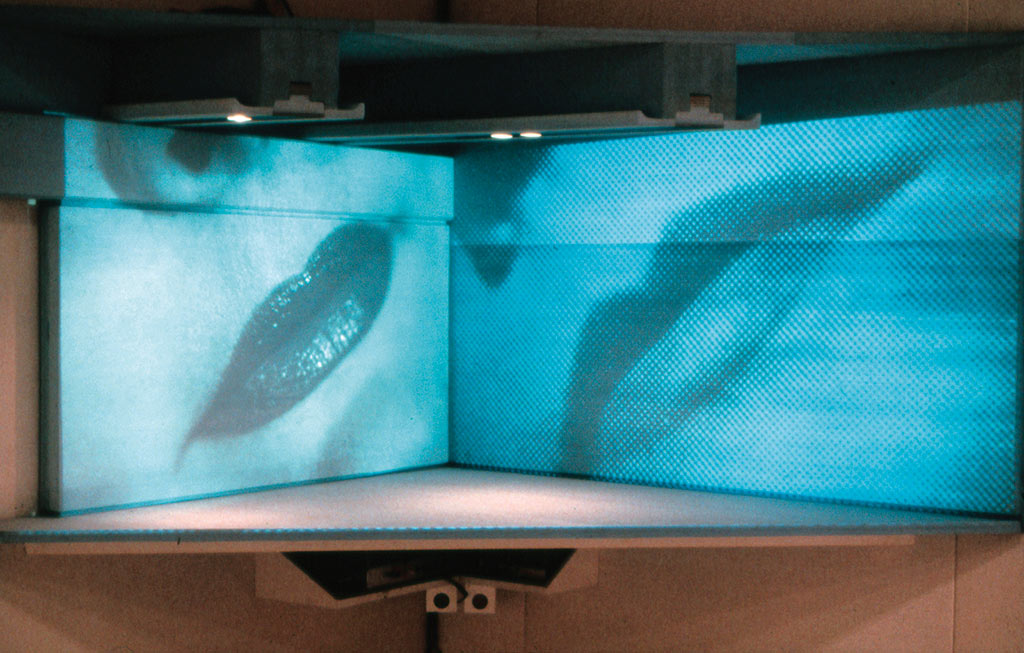

Fee, Fie, Foe, Fumm (detail), 1981

All images courtesy the artist

The information is current to the date when the artist received the Prize; for current information, please see the artist’s and/or gallery’s website.