2012

Kim Adams Born 1951 in Edmonton, AB

Kim Adams Born 1951 in Edmonton, AB

By delving into the ordinary, he has created the extraordinary and rendered its meaning universal.

The appearance of Kim Adams’s work could not be further from the minimal taxonomy so prevalent in the art world when he came of age as an artist. Adams is, nonetheless, a cataloguer of sorts. His idiosyncratic, overflowing installations and fluidly accomplished drawings—created as though by nature or by compulsion—are maximal collections of everyday instances and examples. It is these witty accumulations, all heaped together in fecund exuberance, that have brought Adams acclaim at home and abroad. By delving into the ordinary, he has created the extraordinary and rendered its meaning universal.

When I first came across a piece by Kim Adams, both the artist and his work were unknown to me. I was a relative newcomer to Canada and the encounter stopped me in my tracks. In the summer of 1986, in a citywide exhibition called The Interpretation of Architecture, Adams had installed an early version of Curbing Machine on the busy sidewalk of Spadina Avenue. I encountered this contraption and Adams himself, lounging nonchalantly beside it like some beaming—and possibly roguish—fairground barker. The ‘sculpture’ and the ‘sculptor’ had a refreshingly prosaic presence. Both seemed unusually free from lofty assertion and self-regard. On that weekend afternoon, I couldn’t readily categorize Kim Adams and his Curbing Machine or comfortably place him within a set of criteria. There were the overt nods to Duchamp, to Tinguely, to contemporary performance art—and even to the eccentric Rowland Emett and his comically ingenious machines—but there was something else at play in Adams’s work that was altogether different.

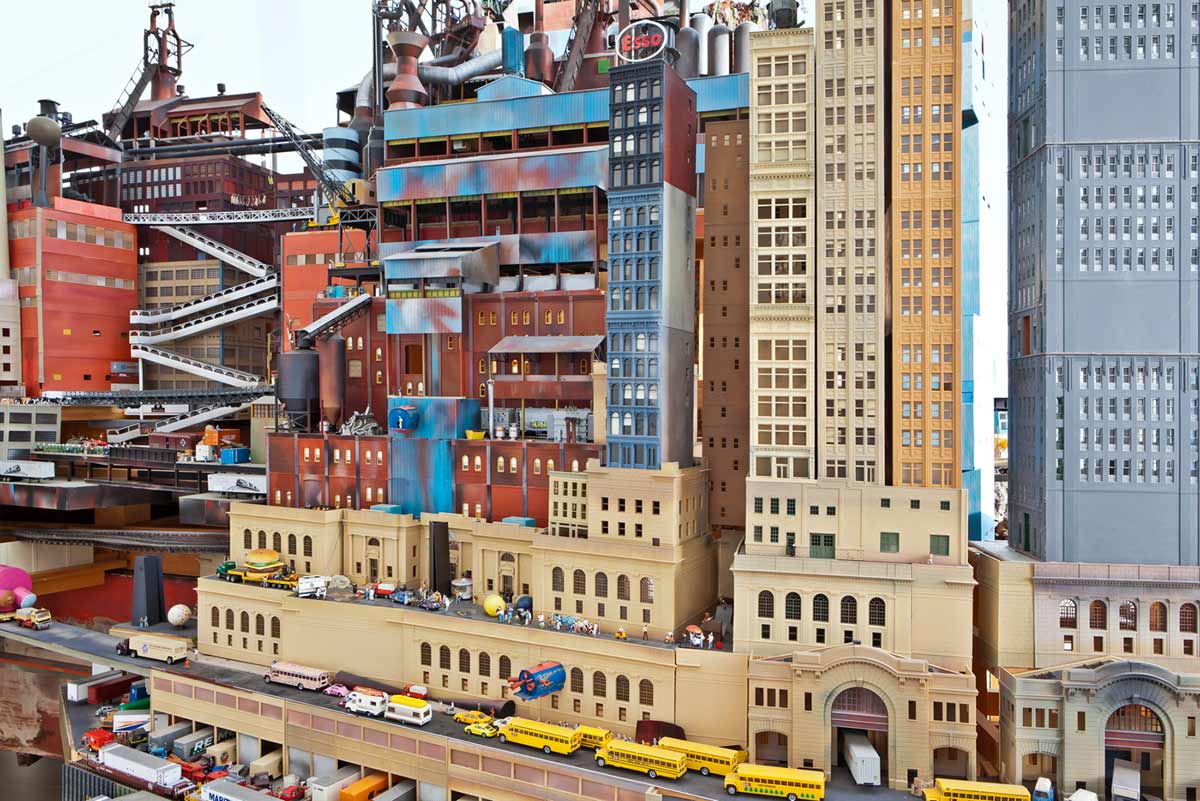

I have since seen many of his exhibitions, have read much about him and have admired the interpretations that have been made. Adams’s true bailiwick, however, remains elusive. The quaint, Middle English term ‘bailiwick’ seems more fitting here than ‘style’ or ‘provenance,’ resonating as it does with the robust energy of Adams himself and with the bustling realms, both real and imaginary, that are central to much of his work. Adams’s energetically peopled worlds—like the Bruegel-Bosch Bus installation, a burgeoning, repurposed Volkswagen van begun in 1996 or the teeming Artist Colony (Gardens) made to mark his 2012 Gershon Iskowitz Prize—can be appreciated as nimbly intentional contemporary equivalents of the rollicking worlds painted by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Hieronymus Bosch and Hendrick Avercamp more than four centuries ago. And thus it is widely accepted that Adams’s hyper-observant, wittily detailed and gently critical catalogue of human activity is a declaration of contempt for our abuse of the planet and its disappearing resources.

But while Adams does seem to infuse his scenes from every day life with the modern equivalent of a moral tale, I suggest that he constructs his machines and builds his playgrounds without comment and without censure. With a compulsive will to form, a child’s imagination, an amoral eye, and uncontained amusement, Adams watches and records—in prodigious spheres of his own making—the times in which we live, for this generation and for those to come. It is his subjectivity, his stream of consciousness, his pullulating drawings and fantastical fabrications, together with their lack of judgment, that render Kim Adams’s body of work so ultimately objective, so fundamentally profound.

Margaret Priest

Ihor Holubizky

Geoffrey James

Margaret Priest

Jay Smith

Matthew Teitelbaum

Bruegel Bosch Bus (detail), 1997–ongoing

Art Gallery of Hamilton

Photo: Mike McNair, Art Gallery of Hamilton

The information is current to the date when the artist received the Prize; for current information, please see the artist’s and/or gallery’s website.