Whittome’s work generates signals, a world of things with her own classifications, series and sequences, and not merely reflections or critique-commentaries on the museum form…

Before the expression “world as a museum” took hold in the cultural lingo—although credit must be given to André Malraux’s Le Musée Imaginaire (1947) and a Marshall McLuhan bon mot from The Medium is the Massage: An Inventory of Effects (1967)—Irene F. Whittome embarked on its actualization with Le Musée blanc and related works in the mid-1970s.

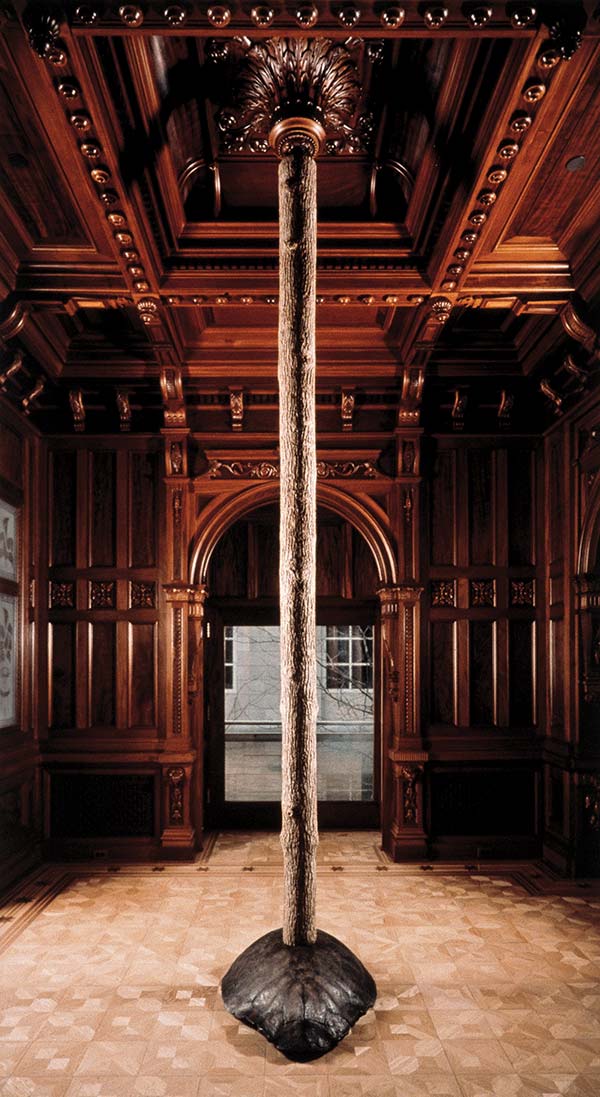

What struck me when seeing one of the works from Le Musée blanc thirty years ago was its quietude. Pole-like elements were encased in vertical wall vitrines, there was a dominant white colour, a ritual wrapping-and-binding, and yet everything appeared found or rescued. It was all the more remarkable in the context of a roughly hewn and chattering group show. Then two years ago, coming upon her Château d’eau: lumière mythique (1997), an elegiac sculpture from a water tower source included in the ROM’s net-cast-wide exhibition Canada Collects, I had a similar experience. This time, the rough-hewn quality was of her own making. It spoke to the idea of “nation” and the museum site as effectively as anything that the museum itself could muster in the grouping.

In between, Whittome produced a tour de force—Le Musée des traces from the late 1980s—which was first shown in a rented garage/storage site in Montréal, and is now in the collection of the Art Gallery of Ontario. More than a cabinet of curiosities brought into the late 20th century—the sight of the giant turtle continues to resonate with me—there is a reverence for things and ideas, for oral history and creation myths, in this work that need not be bound up in the specificity of a dry cautionary tale. Which is to say that Whittome’s work generates signals, a world of things with her own classifications, series and sequences, and not merely reflections or critique-commentaries on the museum form, on what it is or isn’t.

Whittome, of course, is more than her museum installations, but everything I’ve seen serves to confirm that she is an artist who truly bears witness to and considers—to lean on George Kubler’s book and coined phrase—the shape of time. Barbara Black, writing about a Whittome lecture at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts in 2004, summed up her methodology and manner thus: “[It] is a work of art in itself. [Whittome] chooses her words carefully and delivers them gravely, almost like a meditation.” Although not a Whittome-ism, a Kakuzo Okakura phrase from his 1906 The Book of Tea comes to mind: “Let us dream of evanescence, and linger in the beautiful foolishness of things.”

I don’t recall any specific conversation of the jury that awarded the Iskowitz Prize to Whittome, but her name was put on the table. (I may have been the one—not to break any perceived deadlock, but in the spirit of open dialogue.) In an age before Google and BlackBerry, we all relied on our own conversational and (dare I say) intellectual skills, and came to the decision without needing to exercise biases or preferences. A reflective moment in tumultuous times.

Ihor Holubizky

JURY MEMBERS

David Birkenshaw

Ihor Holubizky

Roald Nasgaard

Margaret Priest

Jugement: Principe féminin, 1989

CIAC, Montréal

All images courtesy the artist and Photosynthesis

The information is current to the date when the artist received the Prize; for current information, please see the artist’s and/or gallery’s website.